From Reproduction To Original: Restoration’s Role in Béatrice Balcou’s Recent Paintings

Submitted by sharragrow on

By John Gayer

Brussels-based French artist Béatrice Balcou’s artistic practice focuses on the care of artworks in collections. This, for example, is demonstrated via Untitled Ceremonies, her ongoing performance series. Using written instructions, photo-documentation, white gloves, tools, and ‘placebos’—the artwork substitutes—she highlights processes of unpacking, handling, assembling, presentation, disassembling, and repacking; the types of things museum visitors don’t usually get to see. But in "Recent Paintings", her solo exhibition at Brussels’ Beige Gallery, Balcou’s focus has taken a new direction, by bearing down on what it is conservator-restorers do.

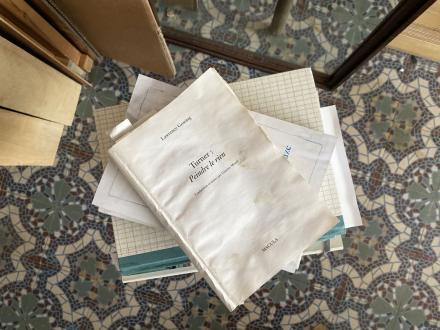

The gallery’s press release, which emphasized this aspect as well as her non-hierarchical approach, stated: “The work of Balcou typically highlights the different agencies that take part in the life of the artwork: the technicians, the registrars, sometimes even the cleaning agents and, in the case of "Recent Paintings", the restorers and in another way the publishers of art books. Balcou therefore levels the playing field between the artist, photographer, editor, collector, printer, restorer.” (Recent Paintings Béatrice Balcou, Beige, Rue Coppens 3, 1000 Brussels, 31 March – 13 May 2023). Consider too that, despite the exhibition’s title, not a single canvas was shown—only damaged reproductions of paintings taken from monographs on Bas Jan Ader, Agnes Martin, Claude Rutault and J.M.W. Turner, objects that conservators treated especially for this presentation.

Moreover, the works’ unique characteristics were not lost on viewers. Questions and comments made in response to the talk Balcou and Francisco Mederos-Henry presented in the gallery, for example, concerned the images’ new-found importance and unexpected consequences. While one audience member asked about their status—Does it now rival the actual paintings? —another proposed that the time and energy put into repairing gives rise to the idea of restoration as a moral act that could, occasionally, become a fetishization (Artist Talk with Béatrice Balcou and Francisco Mederos-Henry, Beige Gallery, Brussels, Belgium, 22 April 2023. Recording courtesy Ann Cesteleyn, Beige Gallery).

I, in contrast, felt it important to learn more about the project’s background. Thanks to Ann Cesteleyn, Beige’s gallerist, I was able to talk with Béatrice Balcou and her collaborators—Francisco Mederos-Henry, Heritage Scientist, Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage Belgium, and Professor of Heritage & Applied Sciences, École Nationale Supérieure des Arts Visuels de La Cambre, and Mathilde Bezon and Camille Jallu, two of La Cambre’s paper conservation students—at the artist’s Brussels studio.

John Gayer: What triggered this project?

Béatrice Balcou: To answer your question, I must mention my other projects, all of which deal with the background of artworks. I have taken the art technician’s role in many of my performances, done a project with an entomologist, and occasionally worked with conservators too. News of my projects usually spreads by word of mouth, and people agreed to participate simply because they liked what I was doing. But for this project, I proposed to deepen my relationship with restorers to see what could happen. The grant I received also enabled me to compensate the students for their work.

During this time, my ideas kept evolving, but eventually the project would focus on paper restoration. Having known Francisco for several years, I also discussed the project with him. He believed that, since I wanted to experiment, I should invite students to my studio and see how things go. Then he proposed two of La Cambre’s paper conservation students—Mathilde, who was in her last year, and Camille, a third-year student.

Mathilde Bezon: At the beginning, Camille and I started doing condition reports and developing plans for images by Turner and Agnes Martin. But on our next visit to the studio, Béatrice had new images for us and that was difficult for us to understand.

BB: Yes, since Mathilde and Camille visited once or twice a week, I continued to think about the project while they were away. Changing things did not make it easy for them. In fact, they had already treated one of the pages, when I decided it would be better to show its verso.

MB: That was one of the most challenging things. Our mending was done on the verso and then, suddenly, it was to be exposed. In one of our discussions, which included the gallerist, there was agreement that this was the right choice. But it was also very interesting to be able to experiment as we did. For the Agnes Martins, we wanted our work to be invisible and, of course, that was impossible. Treating this coated paper was tricky and the success of our inpainting also varied.

BB: This idea to have the verso of one Agnes Martin be its recto surprised me, but I preferred to show that side. That verso had this special quality. But for Camille and Mathilde, who had enjoyed experimenting, the approaching deadline added pressure. Their work would be on view and their professor might come to see it.

MB: We did think these things and felt we needed more time. We had to find good solutions that could be quickly executed.

JG: Complications pervaded this collaboration. Their double sidedness certainly differs from double-sided works of art on paper. You had to come to grips with this to move forward.

Francisco Mederos-Henry: I recall you did want to show the backs at one point.

BB: I did want to show the rectos and versos of a few works, but discussions with a framer were unproductive. And the gallery was so small.

JG: That reminds me of 2001’s Verso: The Flip Side of Master Drawings at the Fogg Art Museum. That exhibition proposed they were 3-dimensional objects.

FM-H: The free-standing structures that support such works can be massive.

BB: I visualized these works more as sculptures than pictures. For me, it was important to see their volume

JG: I found that the depth of the frames and absence of matting do accentuate their volume and materiality. They allow the curling in the paper and juxtaposition of original and treatment materials to show themselves.

MB: That’s the thing with paper. It retains the memory of nearly everything that has touched it. While we agreed to use paper from the same book—not the damaged books, but other copies—to fill losses in some cases, the differences in fiber orientation between the new and damaged pages created tension. Though we tried to reduce the resulting distortions, they remain visible.

FM-H: For which works?

MB: The Rutaults, the Bas Jan Ader, but mostly the Agnes Martins.

BB: For the Agnes Martin with the blue square, the lines in the new and damaged images did not correspond. The difference was tiny, but noticeable.

FM-H: This I didn’t know. How did you solve this issue?

BB: We tried various things, but it was solved by obtaining a new copy of the book.

JG: Did color differences create problems?

MB: No. Things affecting the structure of the fibers—gel washing, drying and flattening—they were the main problem. They caused sheets of the same paper to differ.

FM-H: I think this is beautiful because the reproductions are not reproductions anymore. They have developed an individuality.

BB: Each becomes an original.

FM-H: This is unorthodox in conservation. This project shows how conservators’ interventions combine with artworks to create new material entities. While we like to see ourselves as an invisible hand, we are helping something new emerge from things that have come to us from the past. Sometimes I think an awareness of this would help us change our approach to conservation and the materials we use.

BB: This also concerns the art world. In museums, the captions usually only list the artist’s name, the work’s title and date, and the materials used, not the restorers, assistants or others who take charge of them. I have recommended changes in a few museums, but for practical reasons, the captions must follow a format.

JG: How to best represent artworks via info labels, is a good question. In the course of treating paintings, I have often seen them as composites that, as more and more hands work on them, keep evolving.

BB: And it’s still about the individual’s genius!

FM-H: This is why I like that Béatrice lists the original materials, the degradation materials, and the restoration materials. We, as restorers, tend to only consider the original materials as comprising the body of an artwork, which is not all that there is. The whole timeline of added materials is missing. This project, though, conveys the idea of the object’s lifespan via its materiality.

BB: But without a high degree of precision, so much information could cause confusion. For example, there was a restorer who, while treating one of my wood sculptures, added a piece of plastic to it. And that material is now listed in the work’s caption. While this is part of the work’s history, this detail implies it was I who added the plastic, when it was, in fact, introduced years later.

FM-H: Yes, it’s not easy, but I appreciate how this project offers a glimpse into our world. It offers new ways of seeing how we approach materials, how we restore, and why we restore, because why would you restore a copy, you know? It raises interesting questions.

JG: It seems to be part of this process of ongoing assessment and revision, like what happens in science.

MB: At the exhibition’s opening, a friend and I were talking about restoration, and we agreed that it is not perfectly objective. Since choices are involved, it’s always subjective. But though we know something of science, we continue to be seen as craftspeople. So, I think it’s controversial to say there is no objectivity. The first rule we learn in school is never work systematically, that every case is different.

FM-H: Yes, science has this influence on contemporary society. In conservation-restoration, science has somehow created this illusion that our decisions can be totally objective. For example, this is not original, therefore we remove it. Even though I am a heritage scientist, I am against this binary approach that says things are either true or false. The info we provide to our fellow conservator-restorers tends to support this false view. Science is an interpretation, and some find this difficult to accept. Sometime the pieces of info we provide are seen as the way to go. Restoration hinges on the interpretation of the object and the results can be super subjective.

MB: There were times during the project when we discussed choices and results, which needed to be such and such, where Camille and I thought: this is not restoration. But then we agreed that what we’re about to do, we won’t usually do—that this is contemporary art. It’s what the artist wants us to do. It’s restoration, just not how we’re used to doing it. Here, the losses and the mending would show.

FM-H: You’re saying it’s not restoration because that’s not how restoration has evolved. We decided that mending should not be visible. There was a time in the past when the restoration of paintings by the Flemish primitives were shown in a more archaeological way. The degradations were not disguised. The few still on view in museums look weird. When I first came to Belgium from Mexico, I thought the Belgian way was much more interventionist. But now I’ve become used to that, and when I visit Mexico, I think they could do more.

MB: I know. That’s why using paper from another copy of the same book instead of conservation paper was difficult for us.

BB: I wanted the restorations to be visible from the beginning, but I didn’t know how that could be done. That’s why we had to experiment. I was inspired by Kintsugi—literally gold seams—the Japanese ceramic restoration technique which highlights the joins with gold. It’s a philosophical way of showing the object’s history instead of making it look new. In the end we worked very well together to create something unique.

FM-H: That’s good to know. They were not a random choice. Though Mathilde and Camille’s approaches differ, both are very openminded and curious.

BB: It was really important for me to hear their views, which provided new perspectives on how to proceed.

(Learn more about Béatrice Balcou’s "Recent Paintings" exhibition here: https://www.beige.brussels/beatrice-balcou-recent-paintings/ )

. . . . . . . .

John Gayer is a graduate of the Ontario College of Art, the University of Toronto (BA, art history), and Queen’s University (MAC 1992, paintings conservation), who lives in Finland. He completed a paintings conservation fellowship at the National Gallery of Canada and has worked at the Art Gallery of Ontario, Wimsatt & Associates Art Conservation (Kensington, Maryland), and HAM Helsinki Art Museum. From 2019 to 2021 he served as Nordic Association of Conservators – Finland’s delegate to the European Confederation of Conservator-Restorers Organizations (E.C.C.O.).

(Read the whole article and see all the beautiful images of the exhibition in the October-November 2023 "News in Conservation" Issue 98, p. 10-16)