Book Review: What is Black Art?

Submitted by sharragrow on 25 Mar 2024

Reviewed by LaStarsha McGarity

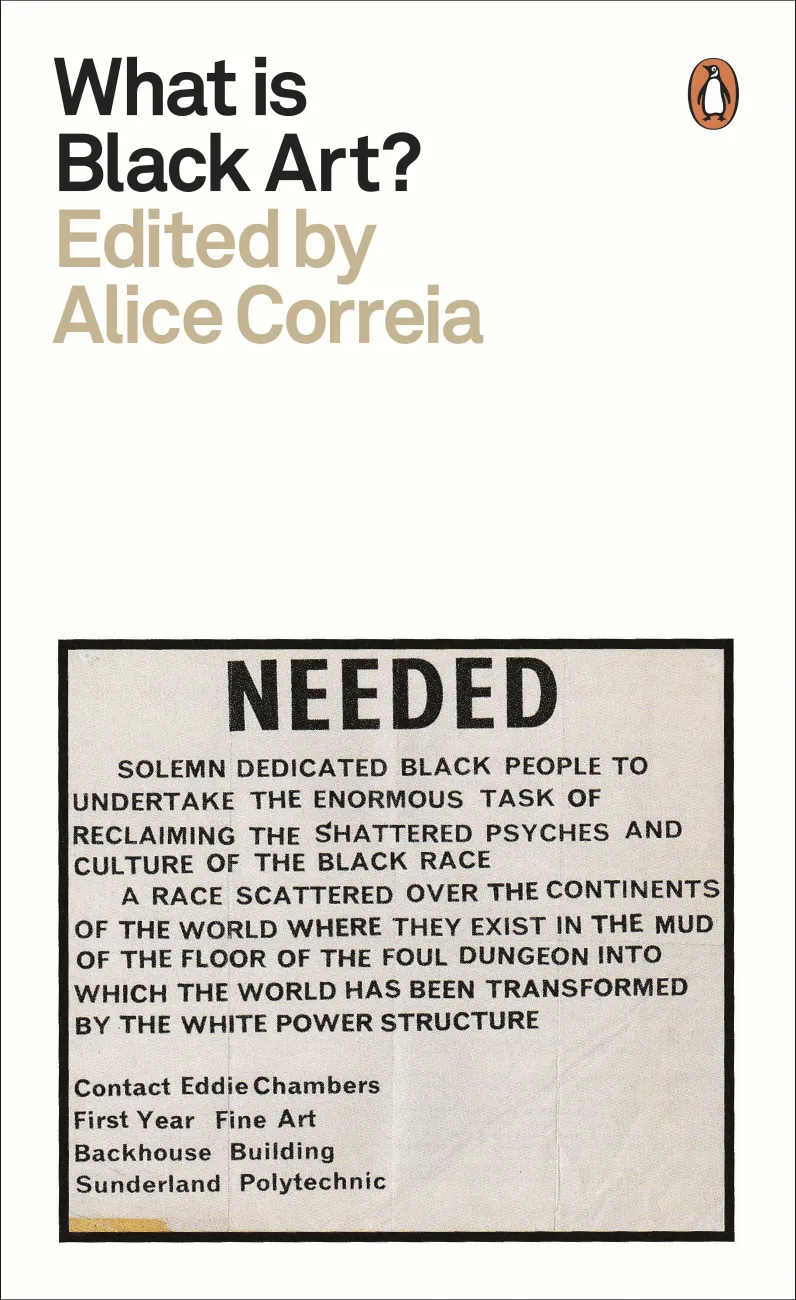

What is Black Art? Edited by Alice Correia, Penguin Books LTD, 2022, Paperback / 352 pages / £10.99, ISBN-9780141998213

Recognizing significant gaps in her art history education and the lack of diversity in British art exhibitions in the 1990s, Alice Correia began exploring what has been coined the British Black Art Movement in the 1980s. This research led Correia to tackle a deceptively simple question, “What is Black Art?,” through the examination of forty-one artists’ statements, articles, reviews, exhibition essays, interviews, and speeches spanning the decade.

These writings reveal layers of intellectual thought, highlight cultural complexities, and humanize the racialized struggles of a rapidly diversifying 1980s Britain. If one is reading this book hoping to get a singular correct answer, expect to be sorely disheartened and frustrated.

Even the definition of Black in 1980s Britain was not as straightforward as one may imagine. Black held dual, often conflicting, definitions: one in overarching foil to whiteness and one centering the dispersed descendants of Africans. Black had been used to describe any person or community deemed not white and was used specifically in Britain to other those of African, Asian, or Caribbean descent. For example, Correia notes that “in Europe, the term ‘Black’ as a racial signifier has a long history dating back to fifteenth-century encounters between Portuguese and Spanish traders and Bantu peoples in sub-Saharan Africa… In Britain during the late 1960s and 1970s, ‘Black’ was commonly—but not always—understood to include people of African, Asian, and Caribbean heritage. Cross-cultural allegiances were fostered by organizations such as the Universal Coloured Peoples’ Association…” (Correia, pg. x)

Black was reclaimed during the 1960s by the descendants of the African diaspora to define themselves as a collective whole, first in the United States, by groups such as the Black Panthers and leaders of the Civil Rights Movement, and later by the British Black Panthers. The latter usage closely resembles the modern term, Person of Color (POC), with its issues of cultural erasure and the lack of nuance alongside its cross-cultural unification and solidarity. As cultural theorist Stuart Hall puts it, “the term [Black] came to provide the organizing category of a new politics of resistance among groups and communities with, in fact, very different histories, traditions, and ethnic identities.” (Correia, pg. x)

Correia expanded on the “collective definition of ‘Black’” as the encapsulation of “strategic alliances and coalitions undertaken by a broad spectrum of people working in opposition to the marginalization, discrimination, and racism they faced in white-majority Britain.” (Correia, pg. x-xi) This overarching definition is the definition that Correia relies on throughout the book, although some of the authors disagree and favor the narrower definition of Black. To add a layer of interpretation, the definition of Black Art could vary from any artwork by a Black artist, about Black people, or by a Black (specifically African descendant) artist working through a politically influenced Pan-African lens. Additionally, some of the authors do not consider works by Black artists that do not center their race in their work to be Black Art but instead label them as blind mimicry and reproductions of white British cultural heritage. Given the compound definition of personal and group identities and artistic classifications, this book has quite the intellectual ground to cover.

Correia masterfully introduces each of the forty-one writings, most presented in their entirety and their original formatting (except when necessary to edit for length, obvious typos, and spelling errors that inhibit reader understanding). Organized chronologically (or as closely as is possible for vague publication dates) from 1981 to 1989, the works document the shifting, imposed, and self-assigned identities of artists living and working in Britain, their collective efforts to increase representation in museums and galleries, criticisms of inauthentic or token representation in museums and galleries, their efforts to control the narrative surrounding their work, and their experiences living in a Britain openly struggling with diversification.

The authors include John Akomfrah, Rasheed Araeen, Imruh Bakari, Homi Bhabha, Sutapa Biswas, Frank Bowling, Sonia Boyce, Chila Kumari Burman, Eddie Chambers, Allan deSouza, Rotimi Fani-Kayode, Coco Fusco, Paul Gilroy, Sunil Gupta, Lubaina Himid, Bhajan Hunjan, Gavin Jantjes, Rohan Jayasekera, Mumtaz Karimjee, Rita Keegan, Yasmin Kureishi, Errol Lloyd, Keith Piper, Ingrid Pollard, Colin Prescod, Samena Rana, Salman Rushdie, Lesley Sanderson, Amanda Sebestyen, Adeola Solanke, Marlene Smith, Maud Sulter, and Gilane Tawadros. Many of the listed authors are themselves artists and are currently receiving renewed curatorial focus and authentic interpretation of their artworks in recent exhibitions along with well-deserved professional accolades.

This book will be an invaluable resource to curators and conservators wishing to understand the context surrounding the contemporary British art field and the interrelations between Black artists, their art, their writings, and the organizations and galleries they formed. Although the contained writings were often not conceived as a discussion with the other included writings, this book reads as a long and enjoyable conversation between intellectual friends.

Author Bio

LaStarsha McGarity (she/they) is the preventive conservator and director of the Legacy Museum at Tuskegee University in Tuskegee, Alabama, USA. She is also a 3rd-year Ph.D. student in the Preservation Studies Program at the Winterthur/University of Delaware Program in Art Conservation. Contact: ldm.objcon@gmail.com

(You can read the review in the February-March 2024 "News in Conservation" Issue 100, p. 60-61)