Regional Live Hub: Africa - plus other highlights

Submitted by Kate Smith on 12 Sep 2022

Ahmed Shayo

As a history student, I find myself drawn to the stories that lie behind the things we see. Quite often, the world around us is filled with so many ‘whys’ that constitute the presentation of the things we see at present. This especially applies in the field of heritage conservation, where one encounters a kaleidoscope of artefacts, both tangible and intangible, that demonstrate the ‘whys’ of a people, and how they have become who they are.

Lamu Old Town is a constant demonstration of this, where its Swahili residency imbues the historic town with a living culture of Swahili traditions from attires and accessories to their language to their buildings, each latter component crowning the other with a finer, unique detail exuded from the former. My exposure to these attributes of the World Heritage has marked the beginning of a passionate need to promote the beauty of existing heritage, while also advocating for the development of our conservation measures which, in the face of increasing climate-attributed threats, demand even more attention to strengthen the Old Town’s resilience to the destructive effects of the environment around it.

In September 2022, the International Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works held its 29th Annual Congress in Wellington, New Zealand, with an aim of bringing together conservators from around the world and holding discussions around the more advanced approaches to conservation practice. This couldn’t have come at a more important moment, especially when the world is rebuilding itself from the plight of a pandemic, that has upheaved the lives of many across the globe. As a selected Digital Engagement Volunteer, I found it imperative to take active participation in the forum, and understand how the more informed contemporaries in this field of knowledge have begun adopting and implementing sustainable practices that will continue to support and value museum collections across the world.

Session 1 - the Opening Ceremony

The opening ceremony was marked with a welcoming of guests and dignitaries to the launch of the event. As is a tradition in the Maori culture, the hosts treated their guests to a mihi whakatau, traditionally conducted in the Maori language. The mihi whatakatau is meant to remove the tapu (restrictions) of the manuhiri (visitors) to make them one with the tangata whenua (hosts). The Māori language is closely related to Cook Islands Māori, Tuamotuan and Tahitian. It gained recognition as one of New Zealand's official languages in 1987. This was to me a remarkable thing to witness, as the act of honouring guests resonates with Islamic traditions entrenched in Lamu Old Town, where guests are treated to dances and poems of praise.

Forbes Prize Lecture

The Forbes Prize Lecture was an introduction to the conservation community for me, as I learned more about work done by conservators, whose efforts to help preserve components of both tangible and intangible cultures have had an outstanding impact not only on the appreciation of the past that have built the heritage of communities, but also the indigenous knowledge that is vital for the sustenance of cultural practices. This was especially highlighted by the works done by James McDonald, whose adoption of recording tools allowed him to record the playing of the lehu nukunuku in 1920. This is perhaps the very first instance of the application of ICT tools in conservation practice, work now more advanced, especially around accessibility of what would have been otherwise inaccessible information on indigenous communities.

This also has resonance with a project I am affiliated with, the Manuscript to Print East Africa Project, spearheaded by Prof Anna Bang of the University of Bergen and Prof Reese Scott of the University of Hamburg. This work has used the adoption of digitization tools to improve how residents in Lamu can preserve their documentary heritage without the fear of ever losing it to the effects of the immediate environment.

Africa Live Hub

This was a live session held on the 7th of September and included a host of African attendees that joined the chat to listen to a diverse panel of authors that discusses topics such as modern approaches to wooden heritage conservation, the transitioning of conservation practices to a performative turn, the development of climate-control strategies as well as the detection of ethnocentricity in conservation practice. Much of the dialogue following the presentations shifted to discussing and interrogating ways that African objects can be repatriated back to their home countries. Discussions also covered the development of synergies between institutions around the world to take effective climate action, and share ideas on how to model strategies that better respond to existing environmental problems around the conservation of artefacts in museums.

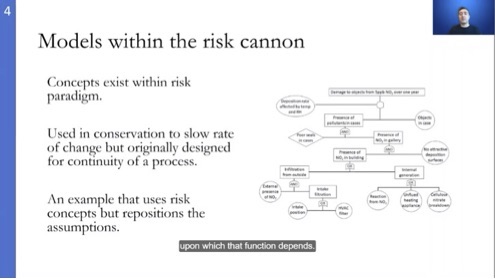

This also provided an opportunity for me to engage with authors such as Joel Taylor, whose input in the paper “Conservation in a Performative Turn” sparked my curiosity about the way in which conservation activities are slowly evolving to accommodate for value-led approaches.