Book Review: Buried by Vesuvius – the Villa dei Papiri at Herculaneum

Submitted by sharragrow on Sat, 18/04/2020 - 16:31

CONSERVATION IN CONTEXT: A TALE OF TWO VILLAS

Review by Graham Voce

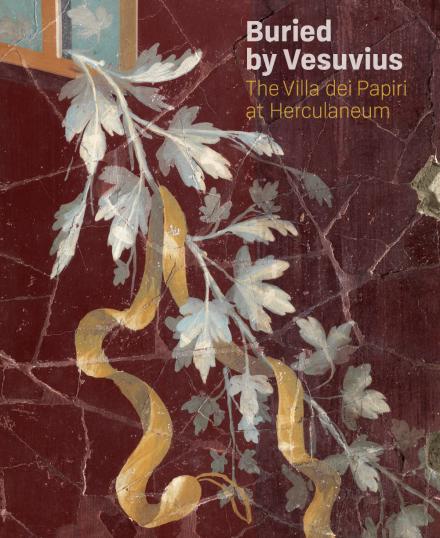

Buried by Vesuvius – the Villa dei Papiri at Herculaneum

Edited by Kenneth Lapatin

Los Angeles: J Paul Getty Museum, 2019

276 pages / $65.00 / Hardcover

ISBN 978-1-60606-592-1

Published to coincide with an exhibition called Last Days of Pompeii: Decadence, Apocalypse, Resurrection at the J Paul Getty Museum in late 2019, this book is very much a labour of love for the Getty organisation as a whole, as this building in Herculaneum was the inspiration and model for the Getty Villa in Malibu. So, the structure and its contents resonate distinctly with the Getty organisation as a whole.

In the Getty’s press release, the book is framed as “the first truly comprehensive look at all aspects of the Villa Dei Papiri at Herculaneum, from its original Roman context to the most recent archaeological investigations.” This book is indeed a rich compendium of investigation and analysis of the original Villa, as well as being a study of the application of the Villa’s story and history to its modern reincarnation in California.

As part history, part survey, part reconstruction, part archaeology, one may ask where the conservation angle is in this rich mix; there is much here for the conservation professional to consider in the story of the conservation of the Villa itself, of the artefacts that have been discovered in the Villa so far, as well as the ways in which they have been conserved and treated since that excavation almost 400 years ago.

The book takes the form of a compilation of papers that accompanied the 2019 Getty exhibition. The first section puts the Villa in its context with contemporaneous descriptions of the eruption and with in-depth explanation of the current understanding of the build-up to, and eruption of, Vesuvius. This event caused Herculaneum, and the Villa, to be covered in pyroclastic flow and lava, and it influenced the ways in which the Villa came to be preserved as it is now.

The second section moves on to the rediscovery of the Villa in the eighteenth century, as well as the then-current approach to conservation and restoration. Also addressed is the fascinating way in which the Italian state hierarchy of the time used the Villa and its contents and treasures to bolster their political credentials and aims. There are also some heart-breaking accounts here, as attempt after attempt was made to open and read the hundreds of carbonised manuscript rolls, most of which were failures despite best intentions. The machinery and techniques that have been invented in several countries to try to read these lost manuscripts are fascinating and arguably constitute an area of study in itself.

The third section of papers together make up a thorough investigation of the structure of the Villa itself (so far as it has been excavated) and of the contents that have been found in it. The quantity of bronzes in particular is quite remarkable, and to see so many of these assembled here is a rare treat. The stories of their various conservation treatments and histories is also very well done. Great attention is paid to the component parts of the Villa itself, from the frescoes to the floors and of course the library of texts discovered there. Again, the conservation content here is a major, but not the only, element of the papers.

The fourth section of the book is about recent approaches to the Villa and its contents, including not only recent excavations on the Villa using modern archaeological techniques, but also the conservation of some fragile ivory artefacts, objects perhaps too delicate to have been conserved in the past. There is also a review of the latest attempts to virtually unroll the scrolls of the Villa’s library. Here we must be grateful to those who, in the early nineteenth century, decided to cease trying to physically unwrap the very charred objects until better techniques were available. Here and now, researchers are experimenting with using analytical techniques such as spectral imaging (with limited success), reflectance transformation imaging (RTI) and, more recently, phase contrast tomography to virtually view the scrolls. This technology could signify the start of some very exciting discoveries when (or rather, if) the scrolls can be unwrapped.

Concluding this book is a paper by Francesco Sirano, looking ahead to what can be realistically achieved at the site of the Villa itself, in terms of both further exploration and excavation, and the conflicting reality of the modern town of Ercolano sitting on top of the site of the Villa and Herculaneum itself. The romanticism of discovery, conservation and revelation is balanced by the pragmatic realities of cost-benefit analyses; realty bites.

In conclusion, this is a fascinating and comprehensive review of the villas, both in Italy and America, and the inspiration of the original Villa is indeed quite infectious and the examinations here very well researched and written. The quality of the illustrations and of their commentaries is excellent and the exhibition catalogue at the end of the book similarly well done.

Conservation is not the prime focus of this book, but the essential part that conservation practice and conservation science have played over the years in relation to this site is a thread that runs throughout the book. This is a welcome and holistic approach to heritage, and as conservation professionals we can be proud to see our place in the past and future of this fascinating pair of mirror sites. Very much worth reading.

AUTHOR BYLINE

Graham Voce was IIC’s Executive Secretary from 2004 to 2020. Having studied both Landscape Architecture and English literature to BA (hons) degree level, Graham is a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries of London and a member of a number of heritage organisations.