Book review: Living Matter: The Preservation of Biological Materials in Contemporary Art

Submitted by sharragrow on

Reviewed by Leanne Tonkin

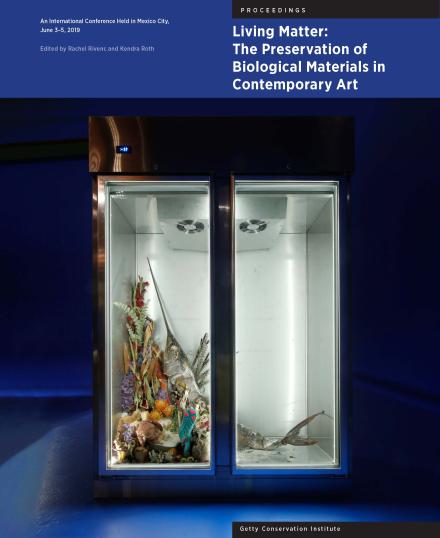

Living Matter: The Preservation of Biological Materials in Contemporary Art

Edited by Rivec, R., and Roth, K.

Los Angeles: Getty Conservation Institute (2022)

Digital publication available here: https://www.getty.edu/publications/living-matter/

This conference was jointly organized with Museo Universitario Arte Contemporáneo (MUAC) of the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM), and Escuela Nacional de Conservación, Restauración y Museografia (ENCRyM) of the Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia (INAH).

Acknowledging the importance of conserving and interpreting bio-based art is a key outcome from the Living Matter conference proceedings. This publication is the first on conserving bio-based materials making it significant in appropriating ethical and archival protocols for biological artworks (Biological artworks are objects that are made with materials that have non-static properties and qualities, introducing different types of material-object interaction within a museum and educational context).

The twenty-four papers presented here reaffirm the past and continual commitment from artists, collections care professionals and others whose practices are dedicated to the trajectories of biological material engagement. These proceedings acknowledge and evidence bio-based art as being part of cultural heritage, confirming the importance of the conservation and interpretation of living matter as well as the recognition of an established era of artists from the mid 20th century onwards. This scenario points to a new documentation system that encourages a less object-based approach for 21st-century conservation practice—one that observes and records environmental influences as part of bio-cultural heritage.

Creating different installations with the underlying comprehension that art does not last forever is one of the different approaches taken by Adrián Villar Rojas (an Argentinian sculptor who explores notions of the Anthropocene) and Sebastián Villar Rojas (a writer). Their keynote paper “In the Unpredictable Garden of Forking Paths” opens the book. It includes beautiful colour images of case-studies to illustrate how a bio-based material palette presents different possibilities for evoking responses from the users of the artwork, therefore creating diverse types of material agencies which entice artists like Adrián Villar Rojas to creatively engage with aspects of decomposition, growth and reproduction. The case studies illustrate how Adrián Villar Rojas’ ideas and artworks can intertwine with characteristics in an often unstable environment, including that of a changing climate.

The first section of papers, “Living Matter in Contemporary Art: Snapshots”, explores what decay may symbolise by contextualising the outcomes of bio-based material change. These changes can be associated with socio-political influences that link to human fragility and ageing as significant attributes in the material engagement of bio-based artworks.

The model of “programmed obsolescence” in María and García’s paper re-evaluates decay as part of biological interpretative practice that enables the continual function of an artwork made with food-based media. This type of diversity in materials raises questions about the meaning of obsolescence and potential values of material engagement with biological processes and trajectories.

Artworks that utilise tissue engineering and biotechnical tools endure a lack of historical classification of partially living systems that acknowledge the growth part of a material’s trajectory, confirming that current archival ontologies simply do not recognise the environmental phenomenon of biodegradable artworks. Harren’s paper highlights the issues of “managing material indeterminacy” in the Fluxus art movement, which calls for theoretical frameworks to support artworks beyond traditional points of reference within museum collections. In addition, conservation treatment strategies are beginning to reconsider the processes of decay when evaluating the characteristics of biomaterials and the intention of the artist. Finally, Hauser’s paper discusses the idea of “object-hood to process-based art” to describe the different practical and ethical processes (and pressures) required for staging, conserving and transporting bio-artworks. The paper highlights the growing requirements to re-evaluate traditional museum and archival protocols to accommodate bio-artworks.

The following section, “Working with the Artist: Between Conservation and Production”, discusses the artist-conservator collaboration while honouring the artist’s practice. Perugini’s paper discusses conserving a segment of human skin taken from Afro-Cuban artist Carlos Martiel. The dehydration and deterioration of the segment act as performative elements that symbolise socio-political influences on segregation in Cuban society. In protecting these types of material integrities of bio-artworks, the importance of collaborative practice is highlighted in documenting broader environmental constituents on objects, like ecosystems, thus encouraging an increasingly proactive approach to the interpretive practice of living matter.

Melleu Sehn’s paper acknowledges the perceptions of unaccepted material characteristics in connection with the environment. Temporality plays a crucial factor in the eco-landscape by challenging traditional acquisition processes that honour traditional long-term commitments in presenting static artworks. This idea connects developing perspectives in academia by evaluating alternative uses of university archives as a learning tool for students and staff, as explained by Mexico’s Escuela Nacional de Conservación, Restauración y Museografía (ENCRyM).

Section three, “Living Matter: Challenging Institutions”, examines approaches to interpreting the material authenticity of living matter in a museum context. The forementioned Fluxus art movement entices discussion about Fluxus artists and the aspect of deterioration in their artworks. Recording the value of an artwork’s end-of-life becomes beneficial to its legacy, as artists work with the anticipation of material change.

Phillips and van der Laan’s contribution considers an “active” and “inactive” framework to assess treatment requirements for living matter within a museum context. This decision-making model shows the process of decay as being an authentic aspect of the artwork. Pragmatic strategies for replacement, replication and reconstruction are components to affect the active and inactive aspects of decay, which is part of the historical context of bio-based materials. This type of decision-making can conflict with traditional archival commitments by museums where objects are often bound to fixed ideas about stability and longevity.

Other papers extend this discussion on material authenticity as an “indispensable part of the design process”, supporting the value of microbiological studies becoming part of the research and documentation of an artist’s creative processes. Oliveira dos Anjos and Melleu Sehn’s paper discusses the system of natural decay associated with outdoor installations, helping to clarify developing criteria for risk assessments for these types of artworks. Further discussion relates to the sensibility and delicate nature of protecting living matter.

The fourth section, “Different Approaches and Responses”, leans towards practical solutions, decision-making models and the call for conservators to take on a more active role in providing ongoing care for decaying artworks. Caring for artworks, like the mixed media work Wirtschaftswerte as described by Heremans and Blanchaert, presents a multitude of challenges for conservation because of the different material types. Proceeding papers turn toward contradictions in applying traditional treatments to known degradable artworks, and the potential changing hierarchies that support the environmental monitoring of bio-based materials. Parisi et al. highlights the importance of documenting the artists’ material engagement in rationalising conservation treatments. This section finishes with an exploration of the effectiveness of consolidants to stabilise food-based artworks.

The final part of the proceedings looks at “Artists’ Reflections” giving the reader insight into three artists and their views, relationships and preferences associated with bio-based materials. Gabriel de la Mora acknowledges the benefit of a conservator’s perspective in understanding the manifestation of his biological and organic artworks to enhance interpretation and maintain his legacy. Kelly Kleinschrodt describes her material engagement with breast milk as a medium that expresses her role as an artist working with the elements of human performance (act of producing breast milk) and biological matter. Finally, Dario Meléndez employs the performative aspects of decaying material to express his criticism of the socio-political state of Mexico.

Considerations surrounding the material conservation, alternative handling, processing and recording of artworks that are anticipated to change, reach an end-of-life and intentionally or unintentionally degrade are beginning to inform new ethical criteria for museums and educational institutions. Fluid thinking seems essential in order to adapt to everchanging cultural environments. Moving towards continual and collaborative relationships with artists and their practice ensures the inclusion of different narratives and perspectives. Developing these relationships may record the expected and unexpected stories of conserving biological materials that inform the essences of authenticity, artist intent to community and environment-based aspects of conserving living artworks. Many of the papers in these proceedings discuss assessing risk and the values of bio-based decay as well as its interpretation for current and future users of museum objects. These considerations challenge traditional approaches to how stability is perceived as an archival and guiding asset to collecting, conserving and exhibiting artworks. It also encourages the conservator to become increasingly proactive within museum hierarchies.

AUTHOR BIO

Leanne Tonkin is a conservator, lecturer and doctoral researcher at Nottingham Trent University. She is examining “The role of the Designer Intent: a post-conservation methodology in the collecting, curating and exhibiting of fashion artefacts made with postmodern materials”. She was programme chair for the Institute of Conservation (Icon), UK, at the International Triennial Conference in 2019, which focussed on the lack of diversity and social agenda in the conservation field.